Author Hassan Alnasir

The Recurrent Loss and the Decline of the Bank: How Do We Think about the (Nakba) from Khartoum?

This contemplation can’t be termed an article or even an idea; it falls within the initial stages of reflecting on the event of leaving Khartoum. However, it cascades freely toward the events of the flood (Tawafan) and the catastrophe (Nakba), trying to build a scene and a location. It allows contemplation towards what can be described as the necessities of learning produced by different contexts, yet bound by them, whether in tragedy or necessity! The necessity of theorising for liberation

Introduction

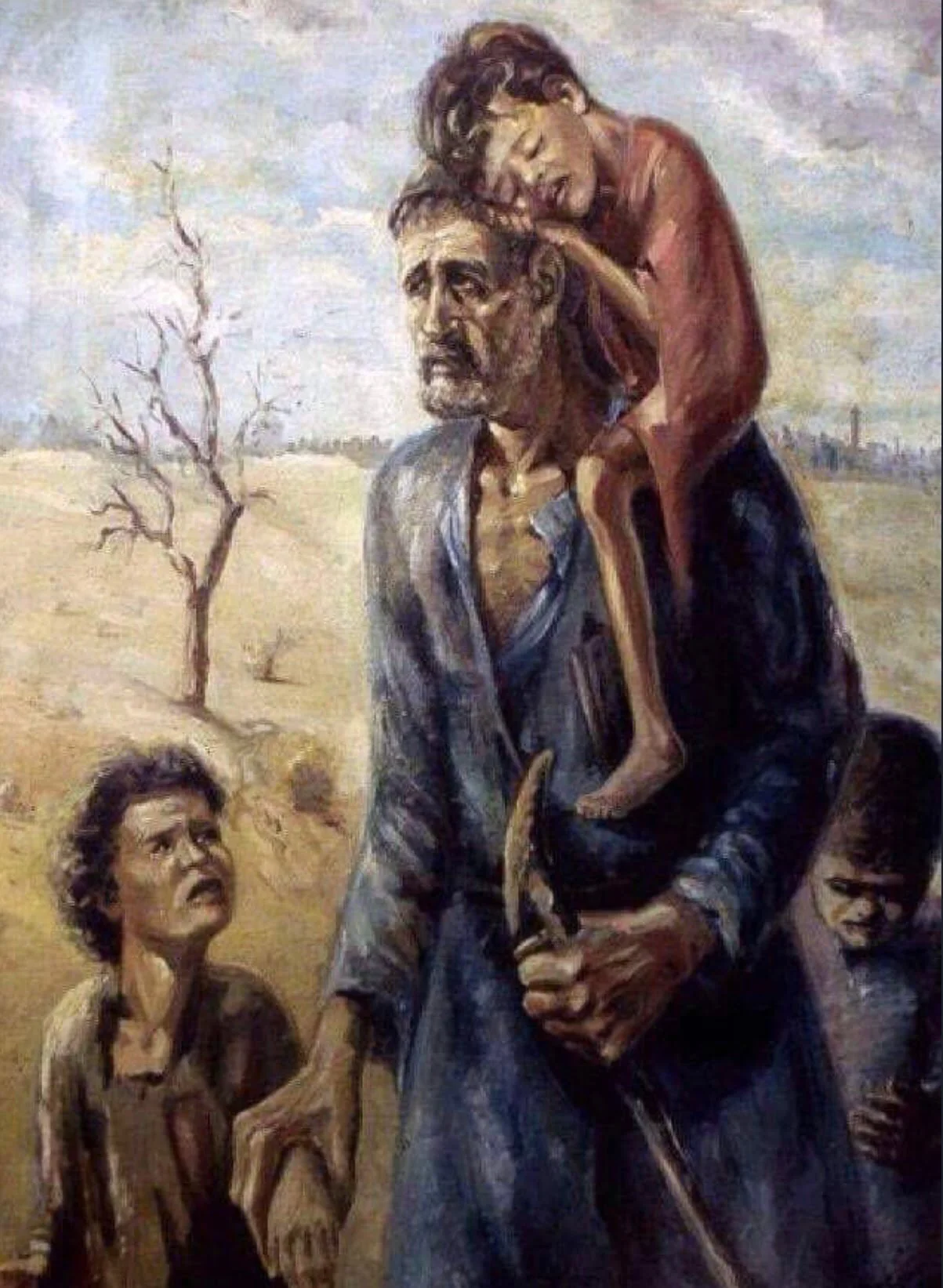

In the southern world, action transforms into an attempt to deceive reality for the sake of resilience or resistance. This is due to patterns that emerged in the shadow of oppression and colonisation, especially the economic transformations in models produced under the umbrella of globalisation. Pain and suffering are transformed into commodities that can be integrated into the market through various institutions. A painting expressing pain, solitude, and migration may become a priced commodity, or music about death, departure, and testimony may also turn into a commodity through views or gaining financial profit for publication. Amidst this belated realisation, the idea of resistance and creating a narrative through which we can deceive this turmoil seeps in. In other words, we work towards adapting/shaping this network to infiltrate resistance as an idea.

The very mediator, i.e. technology itself, becomes a transmitter of the idea of resistance. We outsmart meta-algorithms that delete posts and images related to (غ/ز/ة) as for (Gaza) and (ف..ل…س..ط..ي..ن) as for (Palatine), developing expressive visual images or texts that convey the context of resistance. This is done to affirm the statement and position of the stance, directing our minds toward the tragedy.

The coordinates of perception shift towards resistance, looking to the world not just as a victim of a historical event but as an agent actively changing the flow of events at the communal/individual/social level. It involves reconfiguring the narrative not to shape reality but to express and articulate it.

We cannot separate contexts in worlds that have become open to various forms of expression in which space contracts to zero, allowing us to feel the same pain simultaneously at the same time and in different directions. We are no longer distant and fragmented islands but patches exchanging perceptions and the impactful aftermath of suffering through its transition across the scene, be it in the form of expressive images, text, or audio clips.

Here, we may contemplate an event through experience, not as an opposition or simulation, but through background imaging. This involves revisiting a scene through different approaches. In this imagination, I attempt to gaze at the Nakba (1948 Palestinians leaving their cities and villages), examining how we can perceive it from Khartoum now, as people leave their homes for safer areas during the war of 15 April 2023

This sense is reinforced by the Al-Aqsa flood (Tawafan), where the signs of destruction in Gaza resemble some of the streets in Khartoum, especially the bridges and markets in the heart of Khartoum, which were completely destroyed. This further strengthens the idea of loss/displacement and subsequently enhances the imagination of the return (Al-Aowda). This also parallels the Palestinian memory of the right of return. There is also an intersection in the issue of occupation, as houses were occupied in both cases, intensifying the feeling of being Palestinian in the Sudanese context, especially with the symbolism of the key.

The concept of “Return” has been extensively discussed among Sudanese families who (were) residing in Khartoum after the April 15th war. Most families didn’t carry enough clothes when they left their homes; they didn’t even anticipate that their journey would last for several months. Initially, there was an expectation of a quick return, reflected in literature using the term “باكر/بكرة” (tomorrow). However, families and citizens were surprised to be labelled as (displaced/refugees), prompting some to turn to artificial intelligence to conceptualise the idea of return.

I vividly recall a friend telling me that he carried his house key the same way the Palestinians did during their catastrophe (Nakba). At that moment, I couldn’t imagine that the catastrophe’s reality and the bank’s decline could be observed from the same balcony. Leaving home and carrying a small bag, leaving everything behind, some even forgetting their official documents in the house—no one expected their homes to be occupied or their belongings permanently stolen.

From this, we can say that the bank has slipped, becoming a desire that shapes our memory and for Khartoum to not be those roads or streets but the nostalgia formed by its residents when contemplating the journey of return. While the song that circulated at the beginning of displacement, “يا دروب لوين تودي” (Oh roads, where can you lead us?), reflected the uncertainty of the paths one could take, later emerged the idea of return through the song “بكرة يقولوا عودوا” (Tomorrow, they’ll tell us to go back), conveying the anticipation that tomorrow we will be told to return to Khartoum.

The Nakba might resemble a tectonic event with its epicentre, but its impact has altered various facets in the region and Arab, Middle Eastern, and Southern contexts in general. The Nakba coincided with African liberation movements, showing sporadic and strong solidarity with the Palestinian liberation movement that emerged internally, in the diaspora, and in the regions where displaced Palestinians resettled.

The Nakba has become a rupture in the body of the Palestinian society, shaping the identity of Palestinians. The Palestinian community has attempted to reproduce and reconstruct this event through a series of textual or artistic expressions. One can refer to Ismail Nashif’s exploration of the concept of Nakba in his academic works, where he traced the events of Nakba.

The concept we might borrow to conceptualise Nakba is the recurrent loss suggested by Nashif in his study “Death of the Text,” published in the Journal of Palestinian Studies, Issue 96. This study seeks to identify the features of Palestinian literature based on the experience of literature in the occupied territories since 1948. The author presents a narrative structure model for the Palestinian tragedy that went through three stages: the victim stage, the resistance stage, and the stage of recurrent loss. The study focuses on the literature on recurrent loss within the Palestinian community by defining its relationships and repositioning this community within the overall structure of Palestinian society. The study extensively explores one model of recurrent loss, which has become the most prominent stage from the early 1990s to the present day. It offers a reading of Adania Shibli’s novel, “We Are All Equally Far from Love,” concluding that this novel is, in fact, a manifesto for the death of the Palestinian text.

Using the concept of recurrent loss might be seen as a methodological borrowing, and an academic reader may find it a departure from the context in which Ismail Nashif developed the concept. However, we can employ it in a scenographic approach, transforming the concept into a technique invoked to attempt an emotional exploration within the framework of loss. This could involve portraying the experience of loss in Khartoum or within the Palestinian context, especially during the Al-Aqsa flood battle.

This is not the first time Palestinians have approached their ongoing loss. When the inhabitants of northern Gaza were displaced, the recurrent targeting of residential towers, withdrawal of international institutions, and continuous attacks made them vulnerable to ongoing massacres despite being targeted continuously in the southern part of the strip.

Scenes of families carrying what they can while walking on foot appear as a tableau for the viewer, who is emotionally engaged and pained by the reality of the situation. The thousands of displaced families, with a pallor reminiscent of the 1948 tragedy, seem as if a renewed catastrophe is unfolding. The political discourse has escalated to the point of complete displacement to another location, signalling another impending loss emerging from the dust of the abandoned homes they left behind.

For the displaced/refugees from Khartoum, this scene brings back memories of leaving amid the tension they experience, a mix of longing for their homes and neighbourhoods. This has sparked widespread popular solidarity, creating a nuanced approach between one displacement and the other, an ongoing loss and a new one taking shape. Some friends who left the peripheral neighbourhoods of Khartoum have experienced a second displacement, living through scenes reminiscent of their initial exodus.

Contemplating the Nakba from the perspective of Khartoum adds layers and dimensions to the positional thinking of the Sudanese capital. The question becomes: How do we understand the Nakba? This is achieved through recalling the exodus and scenes of the occupation, then delving into the expression that allows us to witness the decline and return to recurrent loss, which is revisited in the context of Khartoum through nostalgia for it.

From here, it becomes evident that the memory of the Nakba is intertwined with its manifestations in Khartoum, where the event is magnified during the flood, deepening the rift on the outskirts of the city. While we don’t speak of the mediator explicitly, we consider it as a given form, reserved within the acts of recalling and witnessing, forming the approach as well.

Thus, there are three levels through which we can understand how Khartoum and the exodus from it can be the event that redefines the community and society. Through these levels, themes of expression can integrate the experiences of leaving homes and subsequently leaving Khartoum. The medium of presentation can serve as a conduit, allowing the memory to make “the displaced from the city” comprehend the Nakba and re-experience its loss anew.