The onset of war inevitably reshaped the conceptual and political landscape for young artists, particularly those who used to reside in Khartoum or had it as a location of their studios. Many found themselves compelled to flee, both within Sudan and beyond its borders, striving to maintain their creative pursuits amidst precarious circumstances. This emphasis on Khartoum residents is pivotal, as the ongoing conflict thrust them abruptly into the turmoil of displacement. Displacement, a political act of “coercion,” leaves individuals at the mercy of necessities, their options for remaining contingent upon the fluctuating political, legal, and security conditions of the conflicting parties and those influenced by the nature of the conflict, such as countries bordering Sudan.

This situation has put the “Khartoum artist” in a compulsory role of grappling with political themes in their artistic endeavours, navigating the complexities of human rights, legalities, and moral positions amidst political strife. This shift toward political discourse is not only a survival imperative for the displaced artist or individual but also a recognition of the inherent authority wielded by artists to provoke critical reflections on human morality. Simultaneously, it serves as a profoundly authentic means of documenting human experiences, free from the biases of political regimes’ ideologies.

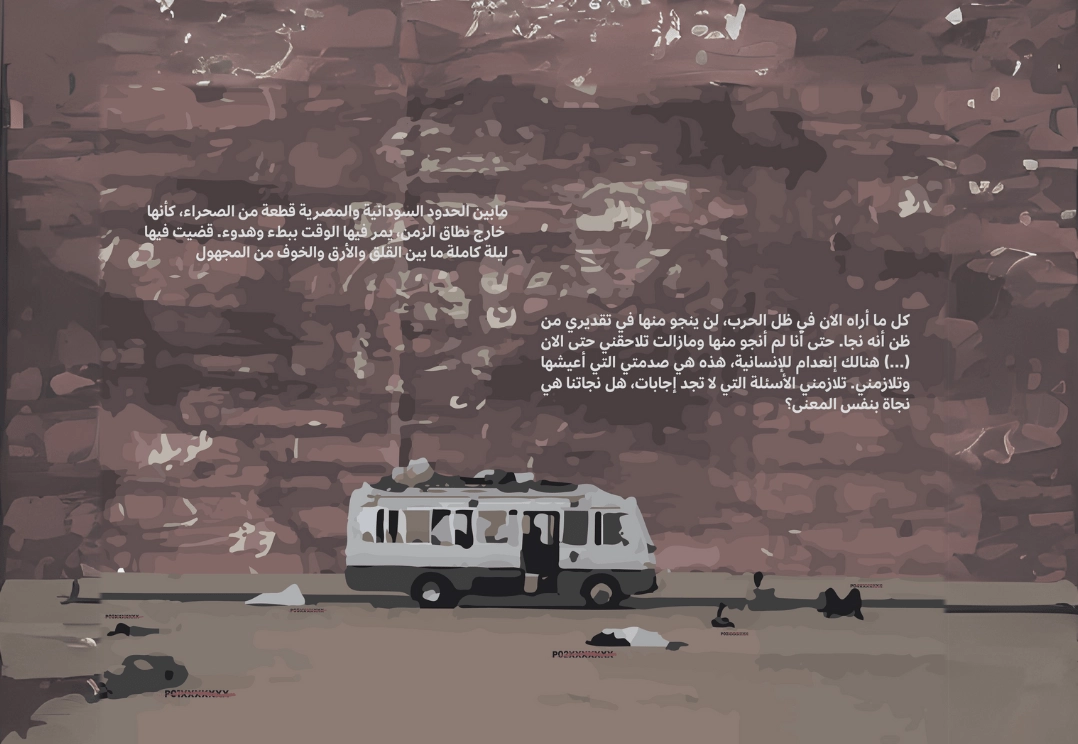

The impact of displacement resonates deeply in the artistic expressions of those uprooted from Khartoum, who persisted in their creative pursuits following the conflict, post-April 15, 2023. Take, for example, Reem Aljeally, who experienced displacement to the Republic of Egypt. She was preoccupied with the idea of the borders between two countries sharing the same piece of land, with “imaginary” geographical borders differing due to national sovereignty claims. In an article published on July 17, 2023, on the website “Khatt 30”, she says: “Between Sudanese and Egyptian borders lies a stretch of desert seemingly suspended in time, where moments linger amidst a backdrop of uncertainty.” The vast expanse between these crossings prompted her to contemplate the ethical and existential quandaries when individuals are reduced to mere statistics or documents by political machinations. Reem poignantly remarks,“You are born human, only to be reduced to a number on a passport,”highlighting how this numerical designation strips away inherent rights and freedoms, subjecting individuals to the whims of state interests. In this context, one becomes merely a vessel for the state’s agenda, devoid of agency or autonomy.

This predicament inevitably thrusts the painter into the heart of ideological contention. Reassessing the status quo and reframing the narrative, whether through aesthetic or imaginative lenses, becomes a means of reclaiming a space of “mental” liberation—a freedom that transcends physical constraints. Additionally, it serves as a testament to the collective human experience amid tumultuous times, capturing both the universal struggle and the artist’s journey within these conflicts.

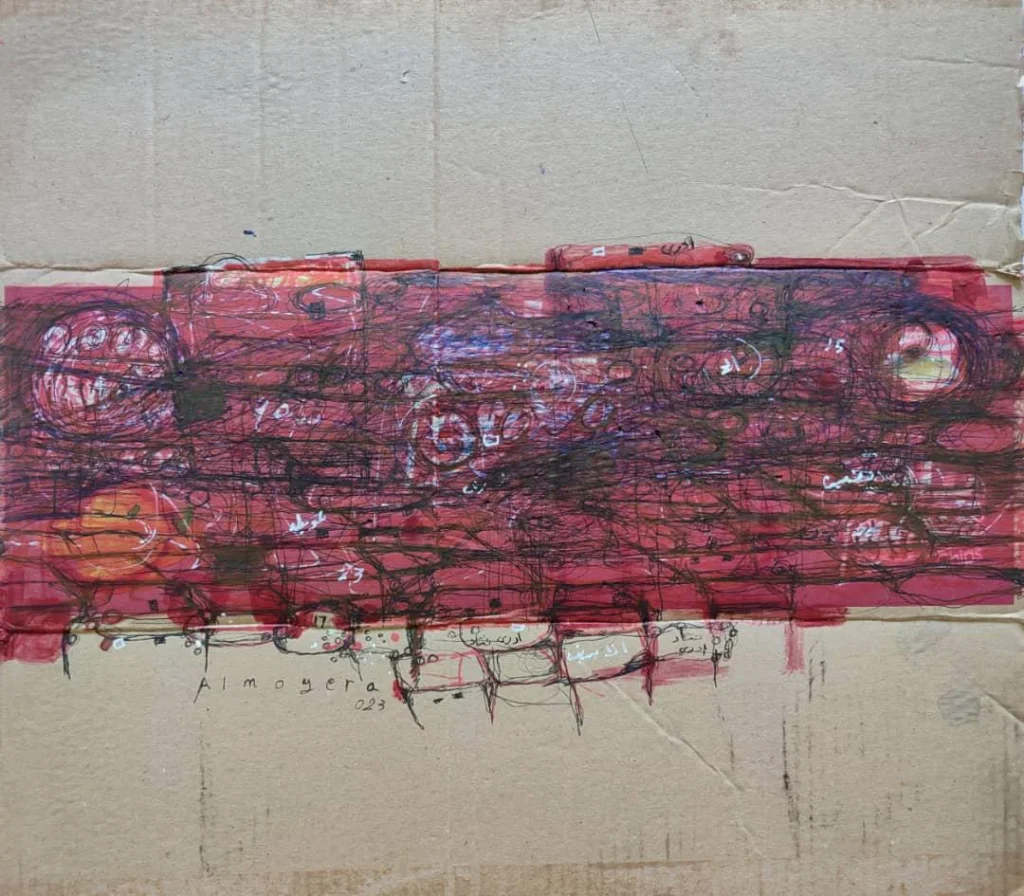

Another example of this phenomenon is to be seen in the experience of artist Almogera Abdulbagi in his exhibition “Najoon (Survivors)” at Kholal Gallery in Port Sudan. Almogera, based in Khartoum (2), found himself entrenched in the conflict from its onset, miraculously surviving multiple direct gunfire incidents, he eventually ended up displaced from Khartoum to Port Sudan in eastern Sudan. In the introduction to his exhibition, which opened on October 7, 2023, he says:

The lens of war colours everything I see now, leaving no aspect untouched, not even myself. The spectre of conflict continues to haunt me (…) There’s a palpable absence of humanity, a reality I grapple with daily. I’m plagued by unanswerable questions—does our survival truly embody survival in its purest form?

The situation of war has confronted these artists with profound existential questions, compelling them to grapple with interpretation, adaptation, and even the pursuit of coexistence amidst the tumultuous aftermath of conflict. I recall the thoughts of the artist Omar Khalil during a conversation about his and his wife’s “Fadwa Sayed Ahmed” exhibition (Exodus of the Soul) on September 9, 2023, at Kholal Gallery as well. When asked about their ability to create the majority of the exhibition’s works amidst the challenges of displacement and the relentless demands of survival weighing upon their family, he said something to the effect of: “Each morning, we would set up our painting supplies and immerse ourselves in the creative process, treating it as a form of therapeutic release—a means to navigate and alleviate the psychological toll of displacement.”

In this sense, the concept of art therapy emerges as a vital means of resilience against the repercussions and aftermath of war. Essentially, it becomes imperative to confront the political and human rights dilemmas of the self, employing art as a nonviolent political instrument aimed at addressing fundamental human inquiries. Art, inevitably situated within the spectrum of available resources amidst turbulent warfare, embodies a crucial tool for navigating and mitigating the profound effects of such circumstances.

This is vividly demonstrated in the artworks featured in the exhibition “Survivors” by Almogera Abdulbagi. Through examining the timeline of their creation, Almogera crafted two pieces while residing in Omdurman prior to departing Khartoum, titled “Khartoum” and “Al Jinaina”. Executed with dry ink pens on cardboard—a resource readily available in such circumstances—these pieces serve as poignant reflections on the realities of war. During a discussion session surrounding the exhibition, Almogera revealed that he spent days immersed in the creation of these artworks, contemplating the ramifications of conflict and pondering potential responses. The act of creation served as both a cathartic release and a means of expression; he would sketch on the cardboard surface, interspersing the imagery with numbers, dates, and words evoking the events unfolding during that period of war. This process, in essence, embodied the essence of art therapy, predating the formal conception of the exhibition itself.

The pivotal factor here is how the tool’s condition shapes the image’s form. In the painting “Khartoum,” executed on perforated cardboard, the central hole bends to convey the “conceptual” void of Khartoum, the emptiness that consumed the city. Likewise, in his series “Survivors,” constrained by a lack of painting materials, he utilized the white space of the paper, creating partial compositions on the canvas. He adopted a technique of using colored lines with a limited palette to depict simple figures and scenes from his experiences of displacement. This approach to imagery and technique marks a departure from Almogera’s previous style, where he filled every inch of the canvas with colors and dense brushstrokes.

What I’d like to emphasise is how the availability of tools significantly influences the form of the final artwork and the artistic results the artist can achieve.

Will the war in Khartoum open a new door for experimentation for artists, experimentation on the level of tools and the nature of subjects? Will they have a new role to play regarding Sudanese political thought in light of what the humanitarian, legal, and ethical conditions will be? Will they have a role in influencing the cultural context to serve their aspirations and visions?

In my estimation, there is a transformation happening in the thought of Sudanese artists and their approach. Since the beginning of the December 2018 movement and the events that followed, they have been at the forefront of political action, advocating for change, and continue to do so, even if war imposes another condition on the nature of their practice.

January 14, 2026

December 9, 2025

May 9, 2025