Since the Sudanese December 2018 revolution, the contradictions of the events that followed were the actions of the “educated civil” elites on whom the people relied in the role of reform. It appeared as signs that indicated the extent to which these elites were estranged from understanding the nature of their reality and necessitated the necessity of a different view towards the social and political concepts in which the interests sought from the act of change converge. It was necessary to see the need to eliminate the dominance of inherited “modern” concepts of form and its consequences in the public sphere. This is by creating new, different concepts that understand our reality and do not deal with these terms with their “common” concepts and meanings, and then installing them within a context that does not resemble them, such as concepts such as democracy, civilisation, the people, etc. It is also necessary to subject them to a critical analysis that deals with these concepts and considers the nature of the conditions and circumstances of the contexts in which these terms arose. To create new concepts that consider the nature of current circumstances and contexts. Especially in countries that have been under the control of “Western” hegemony for a long time and are seeking salvation from their legacy that placed these peoples on a path drawn by the hands of conciliators and self-interests at the expense of the interests of those excluded peoples. This is because (the people of the South did not develop a critical reading of these sciences from the perspective of their local conditions and relied entirely on the criticism issued by Western Europe. They did not reach a sound understanding of their reality and ways to solve its problems)1 or even possess a new definitional angle that guarantees their specificity in dealing with This is amazing.

“Modern” terms and concepts are therefore able to predict the possibilities of their effects in the public space to push their action towards change. And because the effect of that hegemony created an artificial situation under which the “citizen” succumbs, who (in the meantime, leadership has turned into a speck of identity that the security authorities record in their central archive and turn into a number, a fingerprint, and a face. It is a curse on its bearer until the Day of Resurrection. It haunts him every time he tries to He becomes a “citizen,” that is, a partner in that “homeland” that was declared a closed territory in the name of sovereignty, which for us has turned from a legal pride for modern peoples into a security disaster for our peoples who cannot object, neither from within, nor thus fall under the penalty of high treason, nor Resist from the outside, because it will bear the burden of bullying a foreigner2.

According to this situation, in my estimation, two levels emerged that were assumed in how to deal with the nature of the “modern” knowledge imported by the colonises on the one hand, and the dimensions of the effects of this knowledge in the public political and social sphere on the other hand. A level in which the correct reading of the nature of this knowledge itself is often confused. At another level, the nature of its impact on public space. Because reading the nature of circumstances is the product and development of certain knowledge, it varies from reading the nature of its influence; fluence necessarily intersects with the influences of other knowledge, which does not enable the single subject who is familiar with a specific knowledge – linked to his specializasitionto be able to extrapolate the results of the impact of its intersections with the rest of the knowledge in other fields. This was clideenin the fields of arts, especially the plastic arts in Sudan.

بالعودة قليلاً إلى تاريخ بداية ممارسة الفنون “التشكيلية” في صورتها “الحديثة”، نجد أنها كانت نتيجة حاجة البريطانيين لتوفير موظفين لمشاريعهم، لذلك قاموا بإنشاء قسم التصميم في كلية غوردون التذكارية عام 1946. كان الغرض من إنشاء مؤسسة تُدرّس الفنون غرضاً سياسياً يهدف إلى إحداث تأثير مرتبط بالوضع الاقتصادي أو السياسي لبريطانيا في ذلك الوقت. لم تكن فكرة إنشاء ذلك القسم معنية بطبيعة المعرفة الفنية في حد ذاتها بأي شكل من الأشكال.

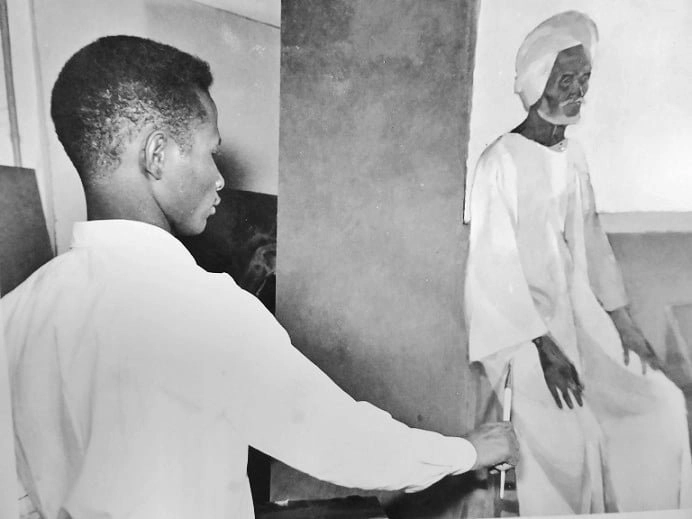

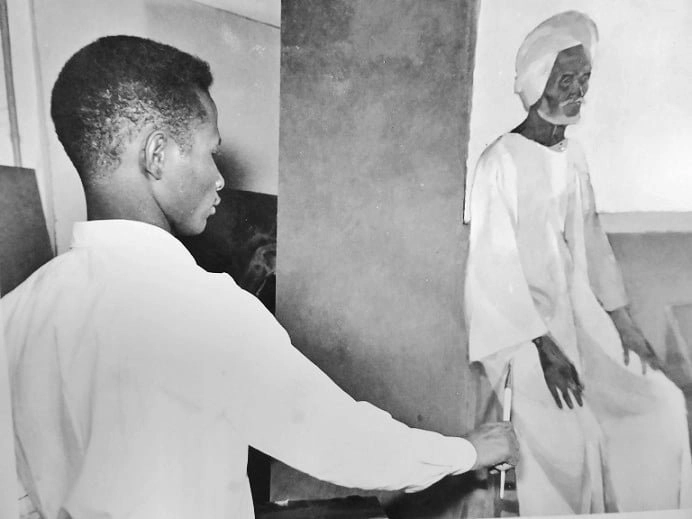

According to this situation, a question arose among the pioneer generation of students at the College of Design about the artist’s social role in cultural identity. It is the type of question that, when we look at it, we find that it stems from a (political) position that carries within it an attempt to know the weight of the social category of “elite artists” within the weights of the “elites” of the rest of the social groups within Sudanese society. Or we find that it starts from the position of the seeker to know the extent of acceptance of his influence in the social space as a necessity that legitimises his presence there. The position of the question in terms of this political and social space assumes a political and social role for the “artist” whose presence in the public space achieves some legitimacy. In other words, this means the feasibility of the artistic product itself. He links the feasibility of his artistic impact to the condition of its impact in the social field. This is a position that neglects or neglects, from the beginning, the nature of individual privacy in the artistic product, which is essentially linked to the artist’s ability to deal with his media “as a mediator who is satisfied with the relationships of his elements” (in the first place) because it is the place that enables the viewer of the artistic effect to evaluate the rise or fall of the level of artistic knowledge3, which is not calibrated or measured by the level of its social or moral impact.

في رأيي، فرض هذا السؤال نفسه نتيجة الواقع الاجتماعي والسياسي للطليعة المثقفة في تلك الفترة، التي خلقت فرقًا، تمثله المسافة التي أنشأها “المستعمر” بين هؤلاء المثقفين وأسرهم التي نشأت خارج دائرة المعرفة “الحديثة”. لذلك، كان التركيز على جدوى تأثيرهم الاجتماعي هو الشاغل الرئيسي في ذلك الوقت. خصوصًا أن المؤسسة التعليمية “الحديثة” في السودان آنذاك قوبلت بمعارضة قوية من الشعب السوداني، الذي كان يخشى أن تحل هذه المؤسسة “المدرسة الحديثة” محل المؤسسات الاجتماعية التي اتفق الناس عليها قبل نظام المؤسسة المدرسية، مثل مؤسسة الخلوة الدينية. كما كانوا يخشون أن تدمر قدسيتها أو قدسية رجالها أو أن تنشر التعليم المسيحي بين أطفالهم. هذا التأثير تسبب بالضرورة في اضطراب أساسي في هيكل المؤسسة الاجتماعية المحلية. لذلك (في رأيي)، أثير سؤال حول جدوى تأثير الفنان في البيئة الاجتماعية من قبل الجيل المثقف كسؤال يحاول تصحيح الإجابة في أذهان الناس حول جدوى ثمرة التعليم الحديث. أو كأن الجيل المثقف كان يحاول تبرئة نفسه من المسؤولية الواقعة على عاتقه بإثبات فائدة هذه المعرفة الجديدة في البيئة المحلية. أو لأن نظرة الآباء إلى أبنائهم “الأفندية” كانت تحتوي أيضًا على تمييز وضع الأفندي في فئة الشخص المغترب الذي خرج من أرض القيم الاجتماعية المحلية. هذا الوضع لاحقًا خلق بين المثقفين موضوعات ظلت تشغل أفكارهم منذ تلك اللحظة وحتى الآن، مثل موضوع “الهوية” على سبيل المثال، ومواضيع أخرى مشابهة جعلت الشخص منشغلًا بالبحث عن خصائص تميزه وتحول سبب حقه في الوجود إلى صفة سلطوية تستند شرعيتها إلى التاريخ والجغرافيا.

It is also, at its origin (the question of the social role of the artist), based on an implicit discriminatory assumption. It means that the educated group is the group that has the privilege of “learning” and the privilege of possessing “scientific knowledge,” and thus, it assumes ignorance among its uneducated people. (The idea of a conscious vanguard that injects its consciousness into the body of the people finds its origins in the history of the national anti-colonial political movement. It is a movement made up of educated people who graduated from the colonialist’s schools (…) This national vanguard that seeks happiness for the people in the name of the people is, in principle, a good vanguard. It tries to tempt and persuade the people, in the best way, to engage in its social visions, but it also has the power to turn against the defenceless people when the contradictions between the people’s visions flare up.4

Therefore, we find that the first educated groups who graduated from the institution (College of Design) took its influence as a political means to demonstrate their social position within the new class conflict, which was produced by the colonial policy among the graduates of its institutions. And to show the size of its class space and its influence within the social space, which is always based on the power of money. That is, demonstrating the material ability among members of society, which in turn determines the level of class power. Therefore, (as an example), we find an explanation in the high prices of the works of the first group exhibition held six months after independence, held by the Sudanese Fine Arts Union, which sold most of its works to foreign ministers, notables, and diplomats, who held the highest social rank according to the logic of material and political power. In a comment by the editor of “Al-Ayyam” newspaper at the time, we find that the poor people visiting this exhibition welcomed it all, and their souls were filled with regret because the prices were exorbitant, the least being five pounds, and their walls would remain bare and idle (sic) because their pockets were empty of stains..5

From this comment, it is clear that the group of graduates did not base their social standing on the level of the works presented by leaving the authority to evaluate their impact on the viewers, despite the possibility of gleaning approval and satisfaction with the works from the commentary. However, in presenting and evaluating it, they relied on demonstrating their degree of favour with the dominant and educated political class that emerged from the colonial experience. Or because the act of “acquisition is a space that tends to attract an elite, distinguished audience, with a high degree of artistic taste, and this is what brings the nature of the person who carries out the act of acquisition closer to the nature of the artist himself because he is characterised by the same previous characteristics”.6

يبدو من الواضح أن فعلاً مثل هذا، في لحظته، يرسم خطاً بين حرمان الناس العاديين (من الناحية المادية)، الذين هم الأغلبية، من التفاعل اليومي مع منتجات مثقفيهم. إنه فعل يظهر أيضاً مستوى الشق التمييزي الذي أنشأه الاستعمار وتركه خلفه في عقلية أولئك الذين نشأوا وتربوا تحت سلطته. لذلك، كانت أهمية تأثيرهم على البيئة الاجتماعية وتمديده بين بقية المؤسسات الحديثة أولوية من أولويات اهتماماتهم.

نلاحظ، في هذا السياق، أن التعرف المتبادل بين الفئات المتعلمة والآباء يظهر الطبيعة الاصطناعية لهاتين المجموعتين. حيث تضع كل مجموعة نفسها في مواجهة الأخرى، وترتبط تعريفاتها لوجودها بتحديد خصائص الآخرين.

But this political concern among this vanguard was not based or arose from any cognitive positions related to the origin or conditions of the nature of the type of knowledge on which they work. That is, it is a concern that arose from an angle outside the nature of their “scientific/read technical” knowledge, and their political stance was not based on it. The nature of the position of the person interacting with the work of art is based on the process of creating the work of art. The position of the creator of the work is different from the position of the one who sees the effect. Any action that seeks (renewal on an “ideological” basis without scientific awareness of heritage is no less dangerous than “tradition”)7. Therefore, the confusion between defining and extrapolating the act of creating a work of art and its conditions, on the one hand, and extrapolating the effect of this act as a phenomenon in public space by defining it (art), on the other hand, created confusion that made the definition and description of the latter a definition of the nature of the act itself. Because considering the nature of any phenomenon requires dealing with it through its location within the political, social and historical context as a fixed nature. That is, it has properties, conditions, and a relatively stable rhythmic effect that enables it to be extrapolated as a social phenomenon or as knowledge that meets a social need that creates for itself some class privilege. Therefore, it is not treated as relative knowledge in itself, linked to the individual ability to overcome its conditions or the limits of its subject. The ability to circumvent or overcome the medium by finding aesthetic or interpretive reasons is the value that we express as (artistic). It is an ever-changing process, and the outcome of its impact cannot be predicted from the beginning. Therefore, it is not possible to describe its impact with certainty or treat it as a fixed and inevitable result that can be extrapolated in a consistent, conscious and guaranteed manner.

تعريف (الفن) هو تعريف الظاهرة ضمن السياق الاجتماعي. بينما تعريف طبيعة (خلق العمل الفني) هو تعريف مرتبط بحدود الذات الفردية التي تنتج وتخلق العمل الفني. لذلك، فإن افتراض أن أي أسئلة (حول الفن) يجب أن تُجاب من قبل الكيانات التي تخلق الأعمال كإجابات ثابتة وحاسمة يمكن التنبؤ بتأثيرها في الفضاء العام هو افتراض خاطئ تقريبًا، لأن طبيعة المعرفة المقدمة من العمل الفني ليست معرفة ذات قانون ثابت. لماذا؟ لأنها لا تعمل على الحدود العلمية المرتبطة بطبيعة وسيلتها، بل إن نتائجها دائمًا، وبالضرورة، تسعى إلى تفسيرات وأسباب وقيمة جمالية وتخيلية. هذه قيمة تتجاوز الطبيعة العلمية والعقلانية وليست ثابتة.

لذا، أقول إن افتراض مجتمع الفنانين لأسئلة تتعلق بالجوانب الاجتماعية والسياسية والأنثروبولوجية من خلال أعمالهم كان في جوهره اختيارًا غير واعٍ، سواء كان ذلك عن قصد أو دون قصد، دون مراعاة لطبيعة المعرفة التي يعملون ضمنها.

We find this, for example, in the attempt of the creators of the “Khartoum School” to ask questions about topics of multiple natures and comprehensive topics to answer them through a partial component, one of the effects of the imbalance that looks at the nature of knowledge from the standpoint of its effect and not from the standpoint of its true nature. We find them trying to incorporate into their works the forms of icons present in the local space to establish a kind of “ideological framework” for Sudanese art based on the idea of (“cultural blending” or “hybridisation” between the Arab-Islamic cultural components and the African components that preceded Arabism and Islam)8. However, they did not notice that by rooting the issue of cultures in Sudan by basing them on a “religious/Arab” and “ethnic/African” basis, they had assumed an ideological framework according to which they classified the components of the culture of societies in Sudan. Classifying people based on belief and not culture is a fundamental flaw because “belief” is a partial system within the overall system of culture. Classifying people within a single culture based on “belief” would tear apart the unity of the nation and create battles that would hinder the masses from realising… The arena of the real struggle against those who waste their humanity (…), exploit their race and falsify their awareness9.

مارس 12, 2026

يناير 14, 2026

ديسمبر 9, 2025