This article aims to explain the work carried out by The Muse organisation during the year 2023. Initially anticipated as a year of progress, but in the second quarter of the year, we were confronted with war and displacement. All infrastructure supporting the organisation’s existence was lost, along with project-related materials. Losing the headquarters, a product of three years of effort, was not easy to absorb, as it represented the space embodying the essence of the institution.

In this article, we will explain how we, as members of the organisation, managed to salvage the institution while collectively experiencing the tragedy of all Sudanese people. We strived to navigate our family situations and secure opportunities for dignified survival amid these challenging circumstances. It was not easy to consider art as a luxury; rather, for us, producing art meant creating possibilities for work in these conditions. The most significant challenge for our colleagues and collaborators was losing everything in Khartoum. Our only option was to work and harness all opportunities supporting the survival of the organisation and artistic production, serving as a tribute to all Sudanese people.

This article also encompasses the potential for future work and outlines the organisation’s vision, considering how Sudan can be envisioned under these conditions. Some may hope for a return, but our focus is not on going back; rather, it’s directed towards the future. Even if Khartoum returns, we aim to be different and divergent from what we were when we left. The concept of return has always been an elitist illusion in Sudanese literature, as expressed by various thinkers and poets, whether returning to history as a wound or to ancestors as narcissistic consolation.

The organisation began to grow:

With numerous projects and planning, this is how the year 2023 started. We aspired for “The Muse” to be a Sudanese foundation that enriches the artistic field and research on arts with a diverse range of ideas. Additionally, we wanted to introduce concepts attempting to provide an understanding and interpretation of social reality stemming from the artistic foundation. We aimed to depict different dynamics of artistic practice, so it was essential to connect art with social research. This proposition was complex, and discussions always arose in this space, yet they were consistently fruitful.

Throughout the year, we aimed to focus on the concept of extensions, meaning that projects are not isolated but interconnected. The idea of extension arose because we realised that no artistic work is detached from its context or unaffected by aligning works, whether in this generation or in the technologies that influenced the piece. For example, the theme of tension and demolition in the “Decaying Bank” project also surfaced in the art exhibitions held at our gallery from January to February, reflecting the prevailing sentiment about the place. This theme needed to appear in artistic works even before the war, depicting a continuous state of unease in thinking about the cityscape.

The organisation began to take shape through projects we worked on. The first project was the artistic residency, where we translated the works of over six artists in the early months, aspiring to have at least 12 artists by the year’s end. We also presented two sides of Khartoum by interacting with the city’s space and history and envisioning its future. Interestingly, the decline of Khartoum coincided with the conclusion of the project scheduled for mid-year.

In addition, we attempted to connect Khartoum and its artistic production with contexts resembling it. The “Extended Cities” project aimed to carry Khartoum’s themes beyond its borders by intertwining them with themes shared with other cities. Essentially, we sought to write and reproduce Khartoum through an artistic approach, carrying these themes to other cities, revealing their features and interactions with Khartoum and other urban landscapes, thereby creating a new perspective for reproduction/understanding.

The moment of War:

We did not anticipate war breaking out in Khartoum, given the calm atmosphere observed in the city’s streets and roads during the month preceding the conflict. Everything seemed quiet and proceeding smoothly, aside from occasional sniffles due to tear gas. Therefore, when the clashes erupted, it felt as if the time for war had arrived in Khartoum. Everything became a predicament for us – the projects and programs we had meticulously arranged.

Caught between concern for family and loved ones، the projects, and the gallery we left just a day before the conflict erupted, everything was in disarray. The teacups were dirty because we believed we would return the next day, but the sound of gunfire disrupted everything, freezing time in a single moment. Khartoum became a land of death and dispersion.

We were disrupted for about three months, and returning to work was challenging amid displacement, leaving homes, and enduring harsh refugee journeys that those attached to the idea of Khartoum as a city and spirit couldn’t bear. None could guarantee their life or the life of their family. We buried many friends who died due to military operations, and we lost everything our families had saved, as well as our future.

Let’s begin:

After a period of settling, despite the displacements through which ideas and visions began to emerge, the organisation began preparing its general vision in June, only a month and a half after the war broke out. Our vision formed with the commitment not to leave Sudan entirely but to produce our work in other regions. The idea was that war should redefine us and redefine Sudan for us. We aimed to weave a kind of art that would stick to the community and not depart from its thoughts and concerns.

Port Sudan was the direction we chose to start the revival of the organisation. In Port Sudan, the goal was not to relocate the headquarters or work independently of the artistic institutions in that region. Instead, the aim was to establish an alliance. The organisation emerged as a strategic goal for our institution.

The idea of artistic dialogues emerged as an attempt to add an artistic tradition in the city alongside understanding the form or artistic work. It allows the artist to initiate an elitist piece detached from the city/community’s general mood. There were four dialogues from August to November.

Dialogue: “On the Margins of the Dark Page” – August 5, 2023: Presented by Hassan AlNasser, featuring Faisal Taj Al-Sir, Al Sadig Mahmoud, and Mohamed AlMutasim. Through this closed dialogue, we attempted to contemplate the issue of war through the logic of art, transforming it into a dark page. We explored how elements of colour and form could intertwine with pain and displacement, addressing the diverse perspectives towards war scenes and the ways to engage with them.

Dialogue: “The Visual Arts Scene in Sudan” – September 4, 2023: Presented by Mozafar Ramadan and hosted by Hassan AlNasser. Through a brief historical overview, we examined the connection between the idea of revolution and the visual practices of Sudanese artists. This approach was juxtaposed with the European narrative of the history of visual arts, placing it within the contextual implications of modernity in the scene of the December movement.

The dialogue “Trends in the Visual Arts in Port Sudan” on October 5, 2023, aimed to provide a general framework for the visual arts and artistic schools in Port Sudan. We explored its themes and concepts, attempting to answer the question of the city’s artistic identity. Through an examination of the artistic practices of local artists, with a focus on the works of Mustafa Hussain Salem and Abu Al-Hasan Madani, we aimed to shed light not only on their artistic experiences but also on their historical significance. Through this discussion, we hoped to bridge the gap between the current scene and previous artistic experiences, creating a shared artistic platform.

Regarding “Decaying Bank,” we decided to continue organising the book production scheduled to be released with the exhibition in 2024. We also planned a technical presentation of the artistic projects to reproduce the event and facilitate access, connecting the context of war with the context previously worked on by the artists. We didn’t cease the possibility of producing the final work, which was eventually achieved at the end of the year.

The idea behind working on the book was to deepen the connection between the artist’s sociological statement and the artistic production presented. It wasn’t an interpretative attempt but an artistic statement wherein the artist worked to reproduce the idea on different levels. Additionally, it involved placing the reader in cognitive interaction with the artist, both as a reader and as an interpreter of the artwork.

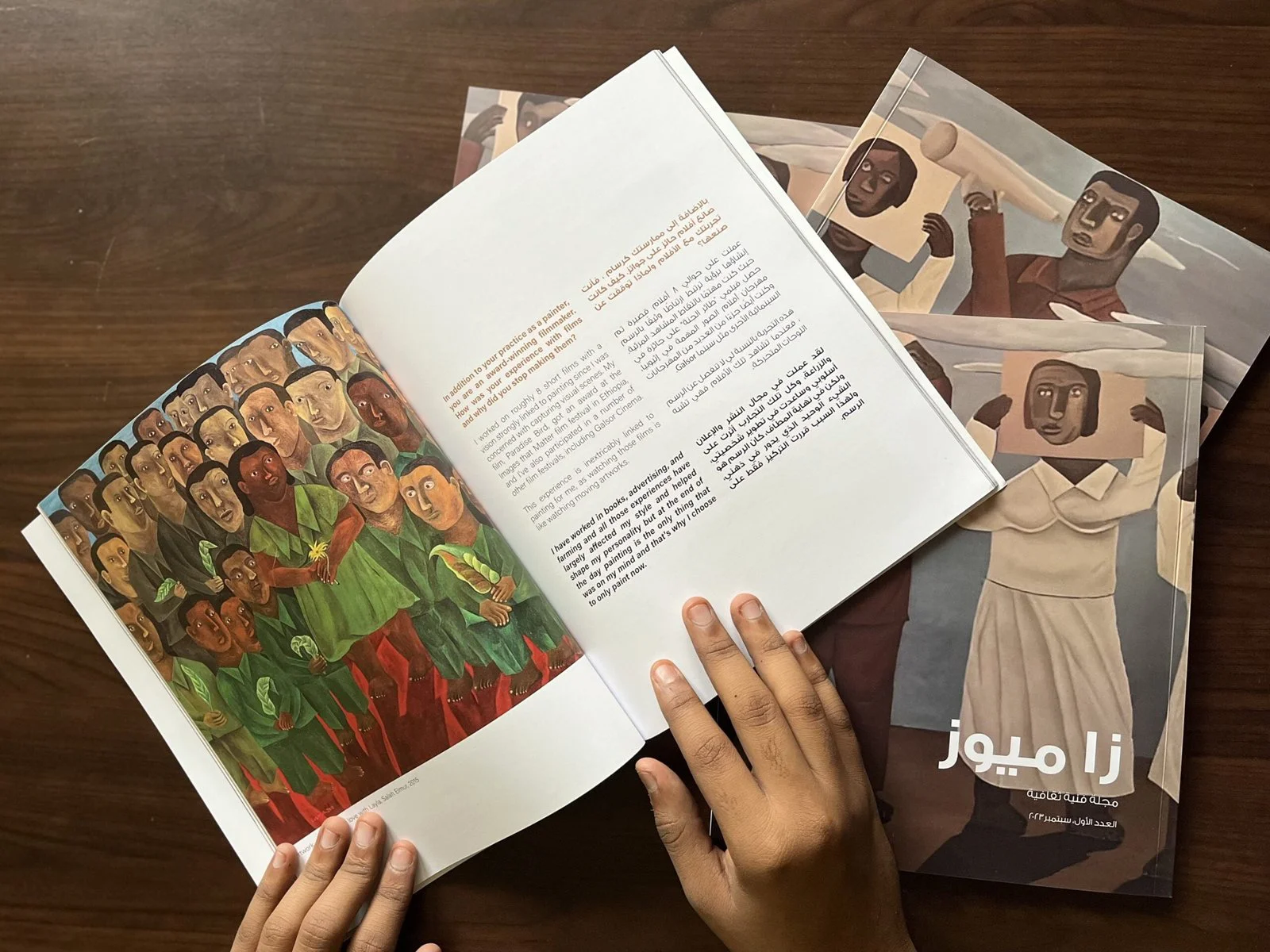

The magazine is an attempt by the organisation to establish the foundations of artistic work in Sudan. It works towards solidifying the “madameek” (stages) of the artistic institution in Sudan, showcasing artistic traditions and practices sought by artists in shaping the visual and artistic space in Sudan. Thus, it serves as a product offered by the organisation to the reader about the art in the Arab world, the African context, and those interested in Sudanese art and its production.

For us, the magazine presented a different challenge as we aimed to frame the artistic intertwining of the artist’s work with the organisation, examining Sudanese art at all its historical levels and the evolution it undergoes.

Moreover, we print and distribute it to the public, aiming to achieve accessibility through the technologies and platforms we use, requiring us to deal with complex technological considerations. The goal was achieved, and the magazine was produced as intended.

Bait alnisa is fundamentally a project dedicated to documenting and presenting female artists in their work environment. Its concept and projects revolve around creating and producing a series of episodes with a group of artists inside their studios or personal workspaces. By focusing on personal stories and the challenges these artists face, the project paused due to intense displacement waves and the loss of workspaces. The project then evolved with a different idea, attempting to conduct remote dialogues with proper documentation of the space, leveraging various technologies and capabilities to achieve the intended purpose.

In the end, it is important to note that the continuation of our organisation would have been impossible without the continuous support of our friends, mentors, partners and supporters, including the Cultural Resource organisation.

Our hopes for 2024:

We hope to head towards Khartoum, as it has become an accessible shore for us. Through our work, we aim to shape Khartoum not just as a recovered space but as a canvas through which we address our vision of the city as a modern space, delving into the complexities of modernity. We aspire in the new year to continue the documentation and artistic archiving of Sudanese artistic production. We work to ensure that Sudanese visual output is not only available but also accessible and not lost.

This year, we hope to enhance our capacity for work and continual expansion, striving for significant progress. The goal is not only for the organisation but to have authentic Sudanese work stemming from artistic capability and will, providing a constant outlet for the aspirations we aim to achieve.